My Cosmology Research - A Pony For My Grandmother

Explaining to my Grandmother what the hell it is that I do

Pony - a literal translation of a foreign-language text, used illicitly by students

Video of Albert Einstein peering through Edwin Hubble’s telescope at the Mount Wilson Observatory. My job was to analyse theories created by theoretical physicists like Einstein and see how well they agree with astronomical data obtained by observers like Hubble.

Video of Albert Einstein peering through Edwin Hubble’s telescope at the Mount Wilson Observatory. My job was to analyse theories created by theoretical physicists like Einstein and see how well they agree with astronomical data obtained by observers like Hubble.

An image of distant galaxies (and some sneaky close by stars…) observed by the Sloan Digital Sky Survey, a group of astronomers that I was part of during my astronomy years. These galaxies are probably much more distant than what Einstein could see with the Mount Wilson telescope.

An image of distant galaxies (and some sneaky close by stars…) observed by the Sloan Digital Sky Survey, a group of astronomers that I was part of during my astronomy years. These galaxies are probably much more distant than what Einstein could see with the Mount Wilson telescope.

Now that I am in final year of my Ph.D, my grandmother constantly asks me when will she is be invited to my graduation party. I have finally decided that it would be May 2011, not 2010, but what I prefer her to ask is: ’What are you working on these days?’. I don’t blame her that her best attempt at summarizing what I do sounds something like ’I have no idea what you do’. It’s not her fault. The common professions are pretty simple to have a basic idea. A doctor cures people, a lawyer helps people get out of a jam (or into a bigger one). Not many know what a cosmologist does. Given that our breed is more exotic than professional athletes, most people have never met an astronomer. So I figure that if I want the people who know me to have a vague idea what and why I do what I do, it’s about time I articulate it in simple terms so, hopefully, they can appreciate what I do with my time, as much as I do.

I feel very fortunate to have find my way (by mistake…), to the forefront of cosmology. I am in the interesting phase where experts are taking my analysis seriously, and consider me an expert on the matter, where only five years ago I didn’t even know astronomy … Go figure… I realize that not everyone can spend their days thinking about and working on things I do, and am very grateful to all my educators who put my on this random, but exciting track.

What I Research: the very Short Version

In the days before Galileo and Newton, philosophers speculated the nature of the world we live in, whereas today, thanks to advances in physics and technology, astronomers can put ideas to rigorous tests. Satellites and ground-based telescopes enable measurements of the Universe, causing cosmology, which was once the domain of the abstract dreamer, to enter the phase of precision science. The expansion of the Universe from a hot soup of particles to the cosmic-web of galaxies we see today, is explained surprisingly well by the“Big Bang” theory. The confidence in the theory stems from analysis of various astronomical measurements, most notably: velocities of galaxies, the cosmic microwave background, and light emitted from distant exploding stars called supernovae. These independent probes agree astonishingly well on many aspects, like the composition of the Universe. Galaxy clustering, the focus of my research, also serves as a crucial test for any cosmological model. Galaxies are not distributed randomly in space, but tend to attract each other due to gravitational pull. The patterns formed contain invaluable cosmological information. One application of this measurement is to determine the energy budget of the Universe. Astronomers have shown that there is more than meets the eye, as atoms, from which stars and humans are made out of, consist of only 20% of the gravitational material. They are certain of the existence of a mysterious substance dubbed dark-matter that has gravitational effects, but does not interact with light. As clustering of galaxies depends on gravity, it serves as a probe of the underlying dark-matter. Combining galaxy clustering with other observations yields the most accurate measure of the energy budget of the Universe, and by so the expansion rate. This, in turn, enables us to determine the age of our 13.6 billion year old Universe to an accuracy of better than one percent.

What I Research (and Why): Cosmology on Very Large Scales

I took on physics in my undergrad as a default, because my application scores weren’t good enough for the more popular engineering I originally wanted. I initially thought that once inside the system I would get good grades and then transfer. Midway through the first semester, though, I realized that I really liked physics. Nothing could be more satisfying than figuring things out, and even more so if its pure and natural. Philosophers use ideas to do so. Physicists do that as well, but they are also equipped with advanced mathematical tools which enable them to actually predict how nature works, and test their theories rigorously. By the time I finished my undergrad, I had no idea how I wanted to advance my studies in physics, but I had no doubt that I am continuing to go on to a Ph.D. There are many interesting details between this decision and actually choosing cosmology, but in brief, the frontier of physics today consists of research of either the very small (sub atomic), or the very large (astronomic), which due to distance, the latter also appear tiny! For example, the moon is huge, but you can cover it with your finger nail because it is so far away.

How far away is the moon? Well, one way to put it is 384,403 kilometers (238,857 miles). A better way of putting it is that it is nearly one light-second away. By light-second I am referring to distance, as opposed to time . It means that it takes nearly one second for a ray of light to go from the moon to a ground based telescope. The Sun is 8 light-minutes away. This means, when you think about it, that when you look at the Sun, you do not see the it at the present time, but rather in its past. If, for example, the Sun should explode we won’t feel its lethal intensity until only after eight minutes past. No need to worry, for the time being, as it has still about five billion more years of fuel to keep it going. The reason I am elaborating the meaning of relationship between time and distance, is to give the reader a feeling of the scales of the universe cosmologists think of in their line of work. Astronomers, in that sense, have a real cool job, because they are the true time travelers. As opposed to archealogists who dig up remnants from the the past and guess what it probably was like, astronomers actually see the past! Let’s continue going up the scale ladder of distance and time. The closest star to us, after the sun, is alpha centauri, four light-years away. Our sun is a standard star amongst hundreds of billions circulating the center of the Milky Way (our galaxy). The center is estimated at twenty six thousand light-years. The closest Milky Way sized galaxy, we call Andromeda, is roughly two and a half million light-years away.

One of the things that fascinated me the most when I started learning astronomy was the vast amount of knowledge astronomers obtained from just measuring light from outer space. I do not know the name of the philosopher who said that we would probably not know what the stars or the sun are made out of, but the man who did manage to figure it out was Hans Bethe. Just before he published his insights, based on the quantum-mechanic tools of the day, legend has it, he was gazing at the stars with his wife and told her, that at that moment, he was the only one on Earth who understands how stars work. Hans combined observations of light with basic understanding of quantum-mechanics, which explains interactions between atoms and the emitted radiation (light) . Nowadays, we measure light coming from all the way back 13.3 billion light years, and use it to strengthen our understanding of the evolution of the universe. The age of the universe is measured (to great accuracy!) to be 13.6 billion years. The origins of light, of course are many, some of them come from galaxies, similar to our Milky Way, that are near (millions of light years) to very distant (billions of light years).

My current research involves measuring the clustering of these galaxies. Galaxies, like our Milky Way, are huge structures of stars (millions to trillions of stars) that formed in the later stages of the evolution of the universe. Just to put things (a little) into prospective, the Milky Way is estimated to contain 100 billion stars, and to be about a hundred thousand light-years in diameter (by now you probably noticed everything is defined by light in this business). Well, how are these huge blobs of stars distributed in space? Randomly like air molecules floating around in space? Randomly but static? Looking at galaxy distribution maps (where galaxies are considered as dots on the paper, or nowadays on one’s laptop screen), we notice, interestingly, galaxies form a cosmic web similar to that of a spider. There are elongated filaments with galaxies, and in between voids, and at cross sections of these filaments huge super clusters of galaxies dominate. The reason for this interesting structure is well understood today. We are in great debt to Newton (who probably didn’t even know what a galaxy was at the time, as this came about to recognition in the 1920’s) and his theory of gravity. Just like the Sun pulls on the Earth, and the Earth in turn pulls on the Moon, galaxies exert gravitational forces on each other and create structures. Just think of pins randomly distributed on a table. Nothing interesting here. Now put small magnets randomly on this table, and you will see structure of pins building up around these magnets. So the filaments and voids of galaxies indicate for us regions of strong and weak gravitational forces.

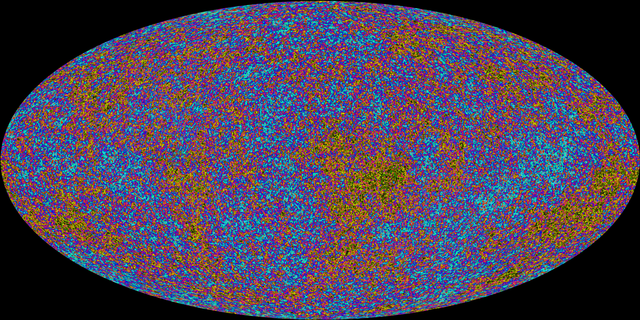

One of the most brilliant scientific feats of human kind: understanding and then measuring the Cosmic Microwave Background. Each red and blue blob is a region of temperature fluctuation as measured in the sky around us. The Universe is at 2.7 degrees Kelvin (near absolute zero) with these small fluctuations which result in the structures in the Universe that we see today, like the galaxy structures.

One of the most brilliant scientific feats of human kind: understanding and then measuring the Cosmic Microwave Background. Each red and blue blob is a region of temperature fluctuation as measured in the sky around us. The Universe is at 2.7 degrees Kelvin (near absolute zero) with these small fluctuations which result in the structures in the Universe that we see today, like the galaxy structures.

The focus of my research is quantifying these sort of cosmic webs and relate results to Big-Bang models. The Big-Bang is a theory that does a surprisingly excellent job at describing our expanding universe. This theory came about in the 1930’s when Hubble related radial velocities and distances to nearby galaxies, and was widely agreed upon in the 1960’s when Penzias and Wilson, two telephone engineers in NJ, discovered the cosmic microwave background that is all around us (we do not see it b/c we only see optical wavelengths and the CMB is in radio frequencies we can only measure with electronic devices). The implications of an expanding universe are many, and the CMB is one of the most important, but here I will focus on my line of research.

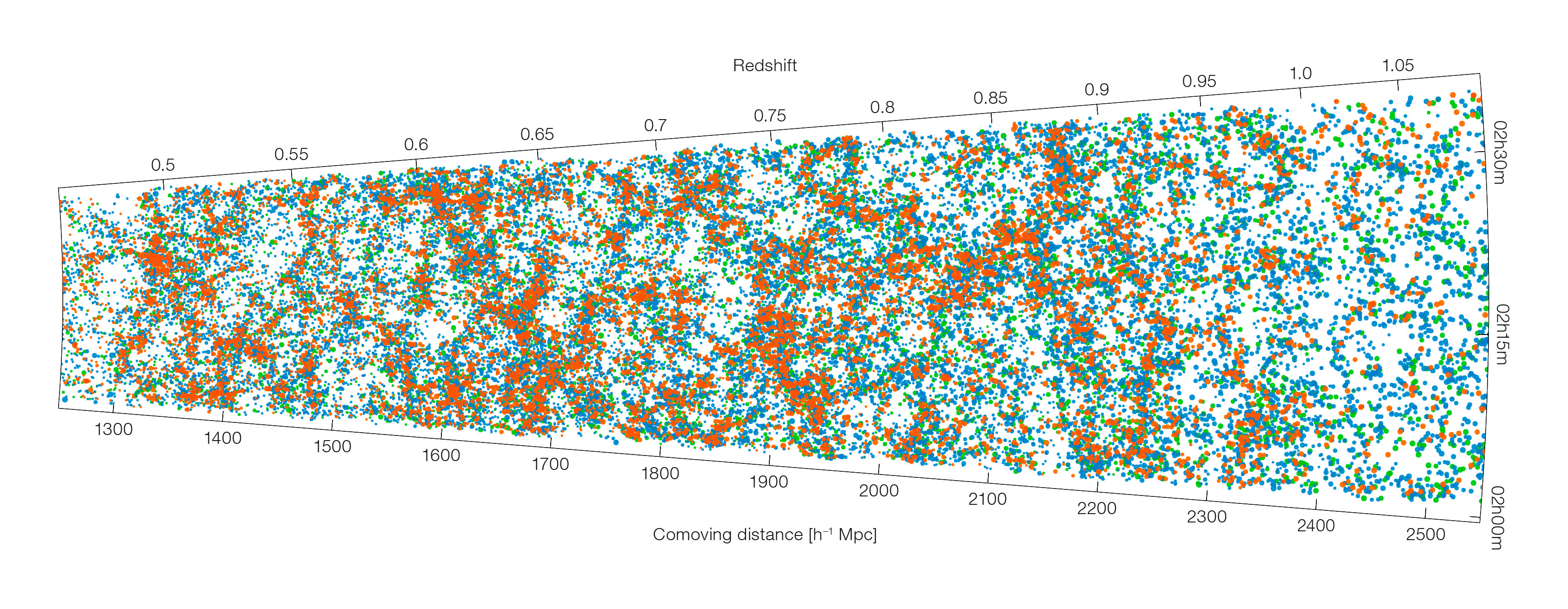

A slab of the nearby Universe where each dot is a galaxy. We can see by eye regions of clustering and empty regions. We call this clustering of galaxies the Cosmic Web becaues of the resemblence of that of spiders.

A slab of the nearby Universe where each dot is a galaxy. We can see by eye regions of clustering and empty regions. We call this clustering of galaxies the Cosmic Web becaues of the resemblence of that of spiders.

In the cosmology ”buis” we refer to the grouping up of galaxies as“clustering”, in a similar sense to the magnet example. Looking at the pins you notice clustering of pins at various scales. If you look at the very largest scales, you will count the same number of pins, as before putting in the magnets (assuming non fell off the table due to clumsiness of the experimentalist!). This means that the overall density (number of pins per unit area of table) is conserved. If you draw smaller circles around groups of pins, or galaxies, you will notice that this density varies, depending on the proximity to the magnets and radius of circle. Closer to the magnet the density of pins grows (more pins per unit area), but if you increase the radius, the more the density becomes more uniform. With galaxies the idea is similar, just that instead of a magnetic force induced by a magnet, we talk about a gravitational force generated by gravitational material like atoms, and another mysterious substance dubbed dark-matter. In the last few decades of the previous century, astronomers have grown to believe in the existence of dark-matter, which is called so because it does not interact with light. So, how does one know what s/he cannot see? Well, if in our example of pins, one would apply a super strong magnet under the table, looking from above you would see something fishy going on, without seeing the magnet directly. The location of the magnet would be the densest region of pins.

Dark matter, hence, are detected by their gravitational effects. For example, regions that contain more galaxies, probably contains more dark matter, as this is needed to bind everything together like pins to the magnet. This might sound like a speculation, but there are many gravitational effects which can be explained by adding dark-matter to the energy budget of the Universe. One more concrete example is that we know that light trajectories get bent due to gravity. Einstein taught us this through his General Relativity masterpiece. Just like a meteor’s path is effected by the weight of Earth when passing by, light rays are, too (though to a much less extent). Astronomers measure the deflection of light, and can estimate the amount of material causing the deflection. Stronger deflection means more massive weight. Counting the weight from the material we see (e.g, galaxies which have stars) does not account for the deflection. Adding underlying dark matter to the equation, though, does! Think of the galaxies as tips of icebergs, and dark matter as the huge rock underneath. The small peak, won’t stop a boat from it’s path much, but attach it to a huge rock, the ship will be seriously damaged and might even sink. You have the right to be sceptic, and physicists are by nature. We are actually living in a very interesting time, when we are sure that dark-matter, which is estimated to comprise of eighty percent (!) of the gravitational budget, is a sure-thing, though we have no idea what it is! By measuring the clustering of galaxies, I am actually helping in understanding various aspects of the cosmos, in which dark-matter is one of them. To name a few more applications, this probe helps understand the expansion rate of the universe, and also interestingly measure cosmic distances! Astronomers have came up with genius methods to measure distances where rulers and lasers are not useful, meaning at astronomical distances. To explain, the moon is fairly close. Astronauts have put mirrors on the moon, and the dynamic distance to the moon is measured by shooting a laser beam back and fourth. We know the speed in which the light is going (the speed of light), so we can calculate the distance. We can not, however, put a mirror on alpha centauri or Andromeda.

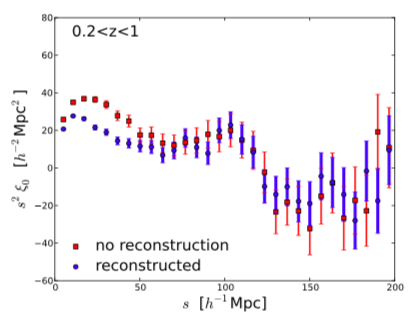

To solve this distance problem astronomers resort to techniques that are based on fairly simple physical concepts. An interesting aspect of clustering of galaxies, is that there happens to be a unique distance-scale. Clustering of galaxies at this unique distance of approximately half a billion light years in radius is a direct result of early universe physics. The basic idea is the following: imagine throwing a pebble into a flat pond. As the stone hits the surface ripples form. Something similar happened in the early universe. The universe was much smaller in the past (remember, it is expanding!), and material was distributed very uniformly, like the calm pond. There were, however, regions with a bit more material. Just like the sudden appearance of the pebble in the pond, this ’more material’, or over-density, was being pushed by radiation causing ripples in the smooth field. This wave propagates for a while, but as the universe expands, at one point the material of stuff (which is actually ionized atoms, meaning protons and electrons), are no longer in contact with the propogating radiation. The material now comes to a stop, because nothing is pushing it forward. Imagine in our previous example that the pond freezes. What we have left is a very unique radius of material (or water). This radius can be traced statistically by looking at distances between galaxies. Recently in 2005, a colleague of my advisor detected this “standing wave” in galaxy clustering. This detection was a huge triumph for modern cosmology, as it reassures our understanding of the universe some 13.3 billion years ago. This detection is also useful, as it can be used to measure distances at cosmological scales. My first publication is a follow up on this study, in which I use a sample of galaxies twice as large. I analyze the clustering of over 100,000 galaxies, and confirm detection of the “standing wave” , and pointed out a few interesting aspects about it that wasn’t previously mentioned.

This is the kind of plot I generated and stared at for years. The bump at the tick mark at value 100 is a beautiful beast - this is the standard-wave. It represents our understanding of early Unvierse physics and its propagation to the recent Universe and its manifestation on the large-scale structure of galaxies.

This standing-wave can be used to determine cosmological distances, as well as measure accurately the composition of the universe, For these reasons many sky surveys are aiming to refine measure- ments of the “standing wave” (very advanced technology and huge budgets of millions of dollars are involved), by probing larger chunks of the universe. Earlier this year I have compled a second analysis on this “standing wave”, in which we look at what has been measured, as well as make predictions for future surveys. These days I am finishing up on a third project, in which I am improving techniques on how to extract cosmological information (expansion rate, distances) from this “standing wave”, and will eventually apply on a new data set that is currently being obtained by a telescope in New Mexico.

I feel very fortunate to have find my way (by mistake…), to the forefront of cosmology. I am in the interesting phase where experts are taking my analysis seriously, and consider me an expert on the matter, where only five years ago I didn’t even know astronomy … Go figure… I realize that not everyone can spend their days thinking about and working on things I do, and am very grateful to all my educators who put my on this random, but exciting track.

Distance galaxies as dots on the screen. This is what the data that I analysed looked like more or less. The reason for the large void is due to survey coverage. The SDSS covered about one fourth of the night sky.

Distance galaxies as dots on the screen. This is what the data that I analysed looked like more or less. The reason for the large void is due to survey coverage. The SDSS covered about one fourth of the night sky.